Lesson 8: Monsters That Hide in Observational Studies

Lesson 8: Monsters that Hide in Observational Studies

Objective:

Students will learn about confounding factors that may impact the results of an observational study, which is why causation can never be concluded with observational studies, only associations between variables.

Materials:

-

Computers

-

Spurious Correlations website (https://tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations)

Vocabulary:

cause confounding factors associated

Essential Concepts:

Essential Concepts:

Confounding factors/variables make it difficult to determine a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Lesson:

-

Ask students to recall that they looked at the relationship between a student’s GPA and the number of friends that person has on social media during lesson 6. It seemed that students with higher GPAs had more friends than students with lower GPAs. But did this mean that the cause of a person’s GPA is the amount of friends they have? NO!

-

They also identified other variables that could have contributed to the relationship, these outside variables are called confounding factors. Remind students that we defined confounding factors in lesson 3 - confounding factors provide an alternative explanation to the effect of the treatment on the outcome variable. In this case, the variables are related to both the explanatory variable and the response variable in an observational study.

-

Propose the following statement to students: “Research suggests that a rise in umbrella sales leads to decreased street crime.”

-

Allow the students to work in teams to think about possible confounding factors. They should choose a variable that is related to umbrella sales, and that might lead to decreased street crime. After they’ve come up with a few possibilities, use the following diagram progression to further explain the impact of confounding factors.

-

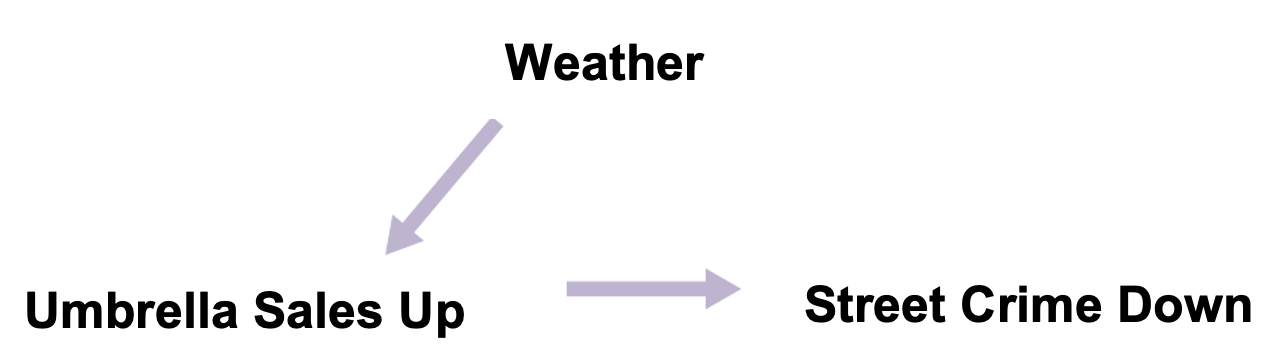

Step 1: Draw an arrow showing that “a rise in umbrella sales leads to decreased street crime” since that is what researchers have stated.

-

Step 2: Include the variable that might be related to people buying more umbrellas (i.e., the confounding factor). For example, when the weather is rainy, people buy more umbrellas.

-

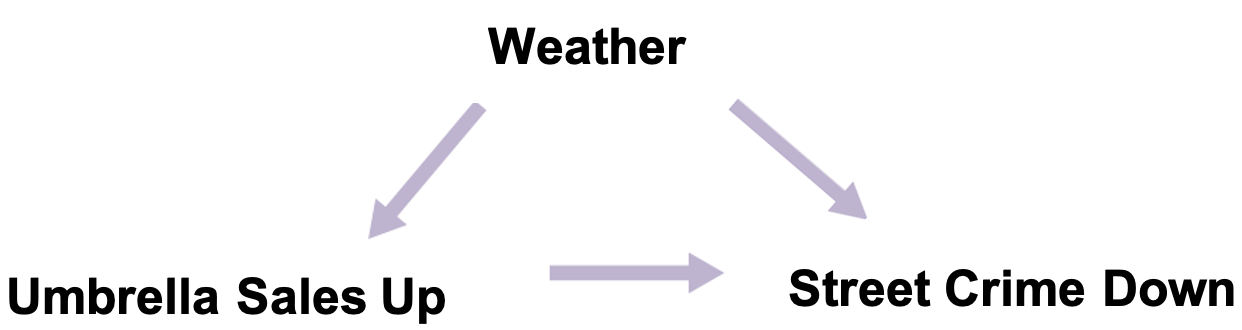

Step 3: Draw an additional arrow from “Weather” to “Street Crime Down” because it is well known that when the weather is bad, people are less likely to be outside committing crimes.

-

Step 4: Remind students that the original claim was that “a rise in umbrella sales leads to decreased street crime.” However, we’ve now shown that maybe buying umbrellas is not the only thing that could be contributing to a decrease in street crime, which makes us question the link between the two variables.

-

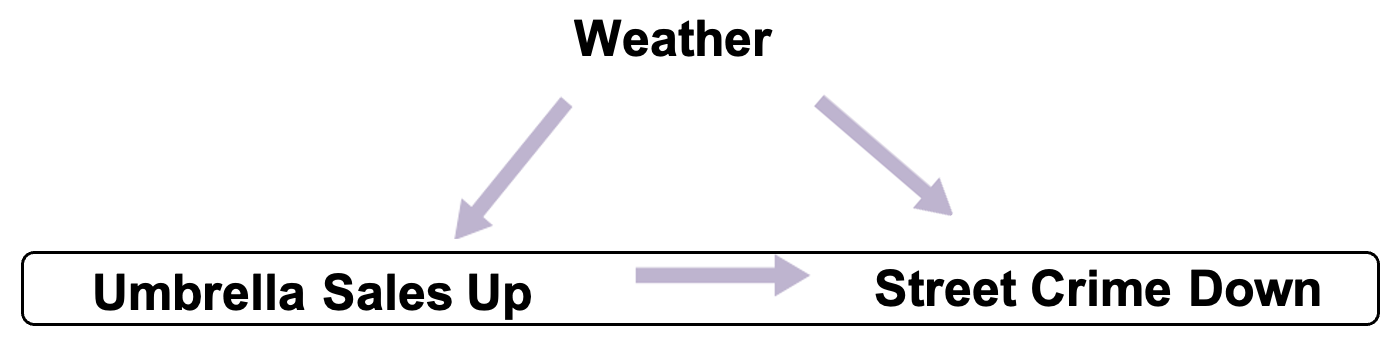

Step 5: Therefore, we have found a confounding factor with the variable “street crime”. This means we can erase the original “link” between a rise in umbrella sales and decreased street crime since there are outside variables interfering. We can’t say buying umbrellas causes decreased street crime, but we can say that a rise in umbrella sales is associated with decreased street crime. We can say that the two variables are associated when the values of one variable relate to the values of the other in some way.

-

-

Once the students grasp what confounding factors are and how to identify them, introduce them to the website Spurious Correlations by Tyler Vigen. This site shows many explanatory and response variables that are randomly associated with each other. Spurious Correlations can be found at: http://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations.

-

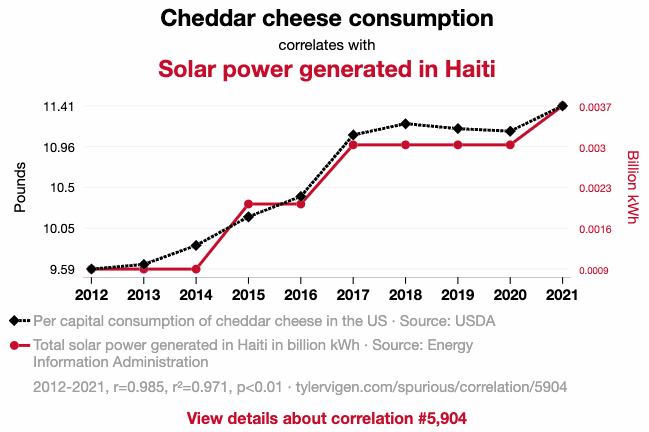

For the example given above, we see that as cheddar cheese consumption in the US increases, solar power generated in Haiti increases. Clearly, it does not make sense that if the US keeps consuming cheese, then Haiti will generate more solar power. It simply happened by chance (or a bizarre chain of confounding factors) that the two variables are related to each other.

-

Allow the students to explore the website on their own. They should choose a graph that interests them and answer the following questions in their DS journals:

Note: There are multiple pages of graphs, so they are not restricted to simply the homepage.

-

What are the two variables shown in your graph?

-

Is there a positive association or a negative association between the variables?

-

Write an interpretation of this plot in the context of the data.

-

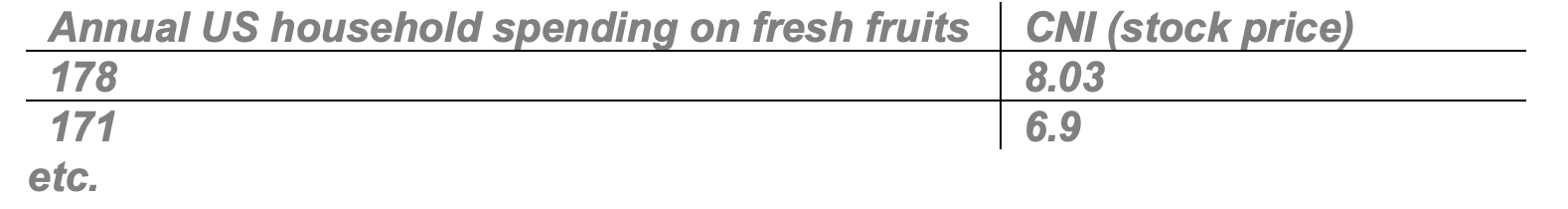

Write the data points in a "spreadsheet format" in a form that RStudio could read. Each row should represent a point on the graph, and each column one of the two variables.

Note: You can get the details about the correlation by clicking on the "View details about correlation #..." link.

-

By hand, make a scatterplot of the association. Describe whether the association seems strong or weak or moderate to you.

-

Do you think that the explanatory variable causes the response variable? Explain.

-

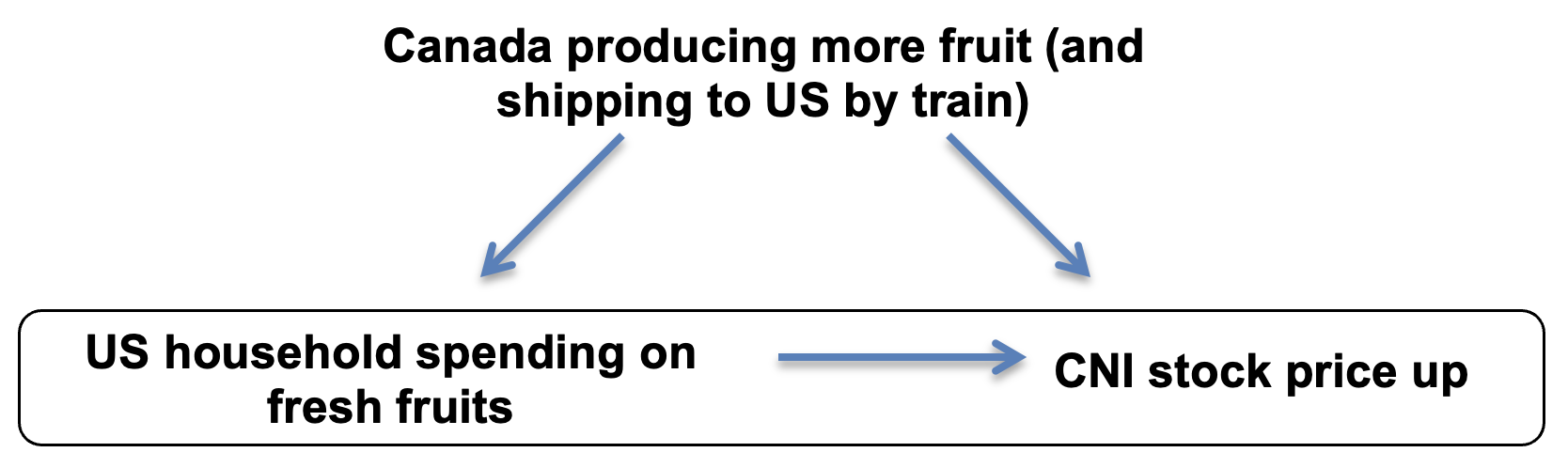

If you answered 'no' to f, then draw a diagram like in #4 with possible confounding factors.

Note: This can be difficult, depending on the graph chosen. Some factors to consider are: weather, economy, fashion trends.

-

-

Example answers to step 7 from above are given below:

-

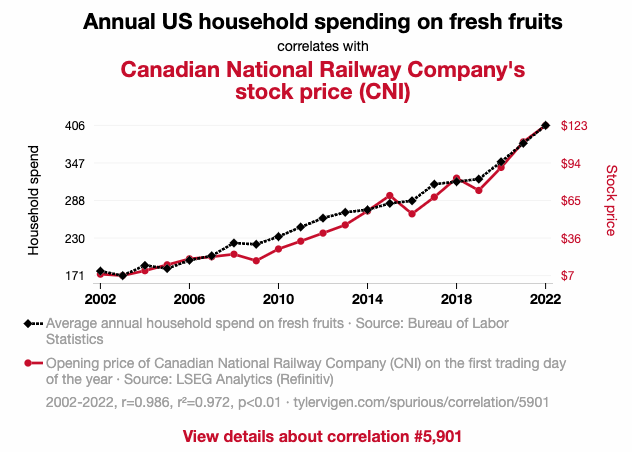

What are the two variables shown in your graph? Answer: Annual US household spending on fresh fruits and the Canadian National Railway Company's stock price (CNI).

-

Is there a positive association or a negative association between the variables? Answer: There is a positive association because the lines have the same increasing shape.

-

Write an interpretation of this plot in the context of the data. Answer: It seems that as more US households purchase fresh fruits, the Canadian National Railway Company's stock price (CNI) goes up.

-

Answers will vary. For this example, clicking "View details about correlation #5,901" showed us the table of data used for the plot.

-

Can you conclude that the one variable causes the other? Answer: No. Although the two variables are associated with one another, we do not have evidence to say that US households buying more fruit causes the CNI price to increase because the data do not come from a controlled experiment.

-

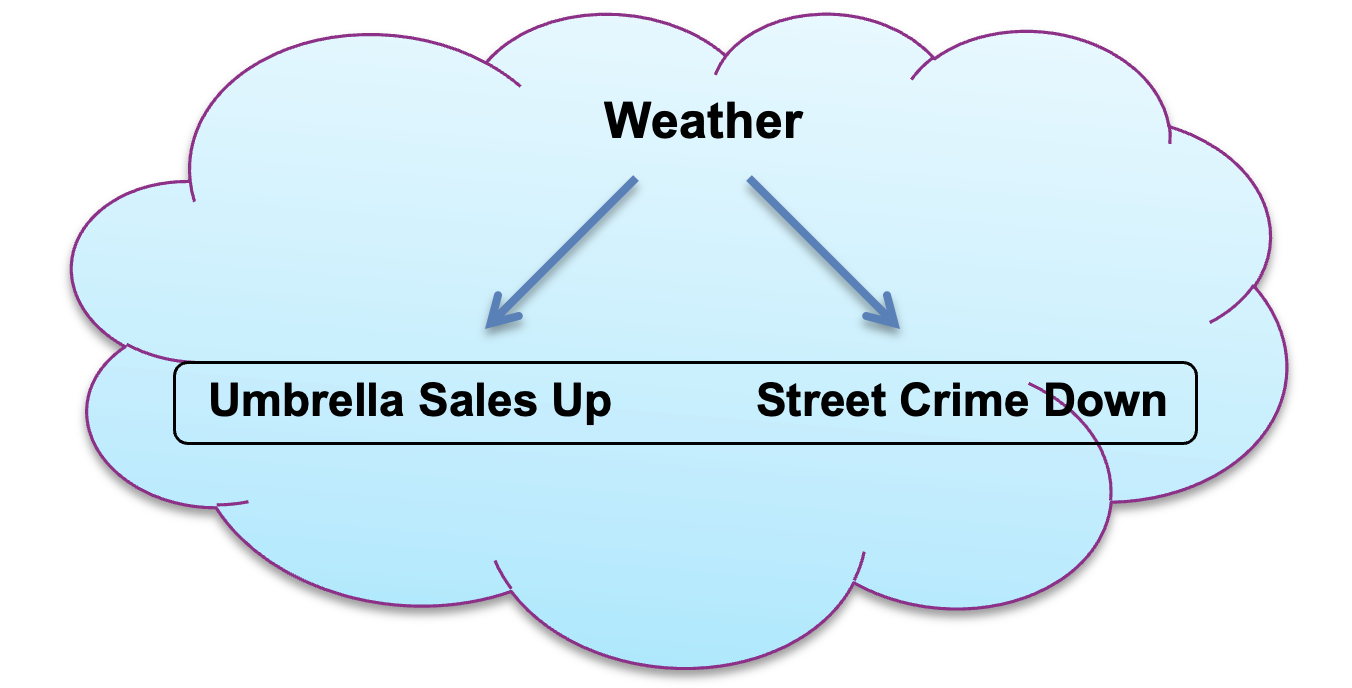

Draw a diagram like the one we did together earlier (in step 4 of lesson) with possible confounding factors. Student diagrams should look similar to the one below:

-

-

Once all students have selected a graph and have answered the above questions, have them share their responses with a partner. They should explain why they thought their particular graph was interesting, how the two variables are related (directly or inversely), and whether or not there is a causal link between the variables.

-

At the end of this lesson, students should understand that causation can only be concluded when an experiment is performed, but associations can be concluded for observational studies.

Class Scribes:

One team of students will give a brief talk to discuss what they think the 3 most important topics of the day were.

Next Day